Choose your own adventure: Mood/Mode

/You’re the star of the story! Choose from 40 possible endings reads the cover The Cave of Time, the first volume in Bantam Books’s Choose Your Own Adventure series. About two years ago, I thought it would be neat to make a piece of music which was guided by choice. Mood/Mode is the first fruit of that effort. The piece consists of an introduction followed by eight possible sections which each represent a mood, an emotion reflected in the music. Each section is based on a different musical mode, a set of notes forming a scale and the basis of the harmony for that section. As the piece progresses, soloists cue the next section by playing a cadenza based on the mode for the next mood. If a mood is repeated, new material is added. Once the final section is signaled, ending music (different for each of the eight moods) is played. There are more than 16.7 million possible sequences for a performance, but at the premiere, we did just two (recordings below).

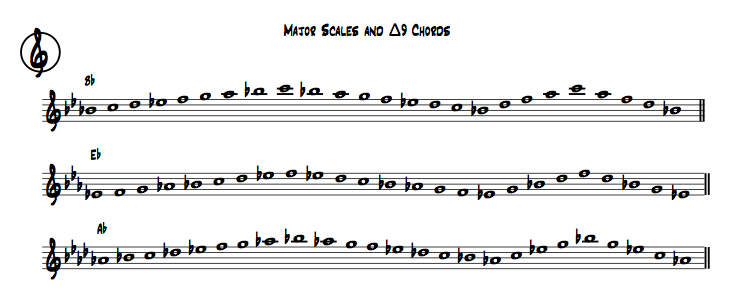

Each student received two pages for their part--one contained the introduction, selectable sections, and endings, while the other showed the eight modes used and a sample cadenza for each. The sections were color-coded (and labeled with the mode name and measure number) to make it easier to see how they were paired (and find the right spot more easily in performance).

The band only had about two weeks to put the piece together from start to finish, and I was still revising up until a couple days before the premiere. The most challenging part of rehearsal was helping the students know what section of the piece was coming next. The soloists did an excellent job of playing confidently and within the mode, but it was tricky to make sure the band would be ready to start playing as soon as the cadenza ended. I found that it helped to give some visual cues to the band (and especially specific players who started a section) so that we stayed on track.

Take a listen and let me know what you think about the concept and the music.

Educationally, there were several valuable things about this piece. It was great to feature student soloists and allow them the opportunity for some improvisation. Keeping the band engaged in listening was also good (and somewhat difficult!). For the future, I would love to spend more time on the modes to help students hear them more quickly. Also, depending on the ensemble, I might want to spend more time discussing the relationship between the modes and moods. With my current Concert Band, we have already done a lot of discussion on this topic (including a seminar on Plato's thoughts on the ways music influences emotions). I picked the moods based on what I hear, but others may not hear as I do.

If you didn't see it on the image above, here are the modes used:

- Octatonic

- Slavic Dorian

- Locrian

- Minor Pentatonic

- Diminished Whole Tone

- Whole Tone

- Mixolydian

- Dominant Bebop